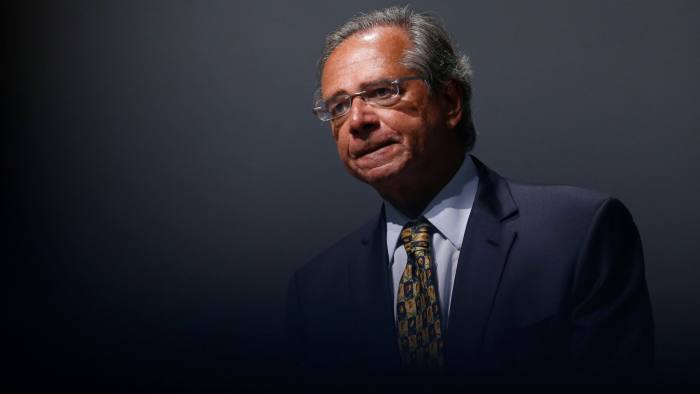

Paulo Guedes touches a finger to his temple. “People from the left have soft heads and good hearts,” he says. “People from the right have hard heads, and . . . ” He searches for the correct phrase. “Not-so good hearts.”

It is a moment of candour for Brazil’s “super economics minister”, given that the president he works for, Jair Bolsonaro, is a rightwing former army captain viewed internationally as something of a proto-fascist with a fondness for military dictatorship.

It is also indicative of the breadth of Mr Guedes’ views, and his belief that Mr Bolsonaro is not the extremist bogeyman he is often viewed as abroad. “We are creating a Popperian open society,” he says, one of several times he recalls the Austrian philosopher Karl Popper — who advocated dynamic liberal democracy — during a wide-ranging conversation with the FT in his Brasília office.

“If Bolsonaro is rough in his manners, it’s just an appearance. He will get rough on the bad guys,” he adds, citing the 64,000 murders Brazil suffered in 2017. That Popper is also a hero of George Soros, the liberal philanthropist hated by some of the ethno-nationalists in Mr Bolsonaro’s retinue, is an irony that seems to escape Mr Guedes.

“Ideology is the real enemy,” he says. “Me, I’m just a scientist doing my job. Everyone has their role.” Mr Guedes, a University of Chicago-educated economist and successful former fund manager from Rio de Janeiro, is arguably the second most powerful man in the Brazilian government, with five ministries — finance, trade, labour, industry and development — in his portfolio. He is certainly the most active.

While Mr Bolsonaro is recovering from surgery, the new administration has been dogged by infighting: most recently, conservative foreign minister Ernesto Araújo sought a harder line against Venezuela versus a more cautious military approach backed by the vice-president, Gen Hamilton Mourão.

By contrast, Mr Guedes’ economics team has hit the ground running with ambitious reform proposals. “Brazil is the world’s eighth-largest economy but the 130th in degree of openness, close to Sudan. It’s also ranked 128th in terms of ease of doing business. I mean . . . Jesus Christ!” he says, leaping out of his chair.

Mr Guedes, tanned, intense in his conversation and with the expressive hand gestures typical of Rio de Janeiro inhabitants, says he wants to cut those rankings in half in just four years by cutting spending, overhauling Brazil’s byzantine tax code, slashing red tape, and privatising state assets.

Born to a lower middle-class family, Mr Guedes schooled himself via scholarships and won an economics PhD at the University of Chicago. Later, he worked in Chile during the Pinochet dictatorship, leaving Santiago with his wife only after he found secret police searching his apartment.

“I saw Chile poorer than Cuba and Venezuela today, and the Chicago boys fixed it. Chile is now like Switzerland,” he says, dismissing social costs such as a 21 per cent unemployment rate in 1983. “That’s rubbish,” he says.“The unemployment was already there. It was just hidden inside a destroyed economy.” It is a contentious view.

Returning to Brazil, he became a fund manager, occasional day trader and prolific newspaper columnist. He says he met Mr Bolsonaro “exactly one year and one month ago” and, after eschewing several government job offers before, uses trader’s jargon to justify his choice now.

“I spent my whole life generating [the market outperformance of] alpha and watching successive governments destroy beta,” he says. “Now I want to improve Brazil’s beta,” using the Greek letter that describes underlying market performance.

After 20 years of dictatorship and 30 years of social democracy, Brazil’s swing to the right is healthy, he says. “When liberals come, it is good news, not bad news.”

Still, doubts remain. What about social policy, given Brazil’s gaping inequality? And is his free market wizardry compatible with political liberalism, given Mr Bolsonaro’s apparently authoritarian streak?

“Certainly. Russia and Brazil had glasnost before perestroika,” he says, referring to the policies of political and economic opening or liberalisation. “You need to have both. Then you get growth, and a middle class that brings stability.” The alternative path taken by Brazil leads to a rentier state characterised by corruption.

“We were a one-legged democracy,” he says. “The system is corrupt. I mean why did Lula, Brazil’s most popular politician, just get 13 years for corruption charges?”

He points at a television, where a news show has just relayed the latest judgment against the former president. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has already been sentenced to 12 years in prison. Critics say this was the result of a politically rigged judiciary that wanted to ban the leftist leader from the election race, so opening the way for Mr Bolsonaro’s win.

Instead, Mr Guedes suggests it was Brazil’s ingrained system of patronage that ensnared him. The recipe to correct this is “a market-driven economy instead of the failed dirigiste economy that corrupted the political order”. Few Brazilians would disagree with that diagnosis given how the country still suffers the aftermath of its deepest ever recession and biggest corruption scandal.

His economic vision is more Ronald Reagan than Donald Trump, and he appears realistic about its political constraints. “The president [can always say] no, I have the votes.” A theoretical economist aiming for the stars, he seems content to reach the moon and admits it will be a bumpy voyage. “Yes, the economy will grow faster. But we can’t be naive. There is a lot of damage to repair.”

Information from Financial Times.